From: Tuscon.com

Under state law, marijuana sold at Arizona dispensaries has to be tested not only for potency levels but also to ensure the drugs are safe for consumers.

That testing provides consumers with information they can use to purchase the type of marijuana they want safely since marijuana that has higher levels than allowed of such things like herbicides and pesticides cannot legally be sold.

And while the legislation doesn’t require that growers, producers or dispensaries label those products with the results, every item sold in a dispensary in Arizona must have an accompanying certificate of authorization that attests to its potency and safety.

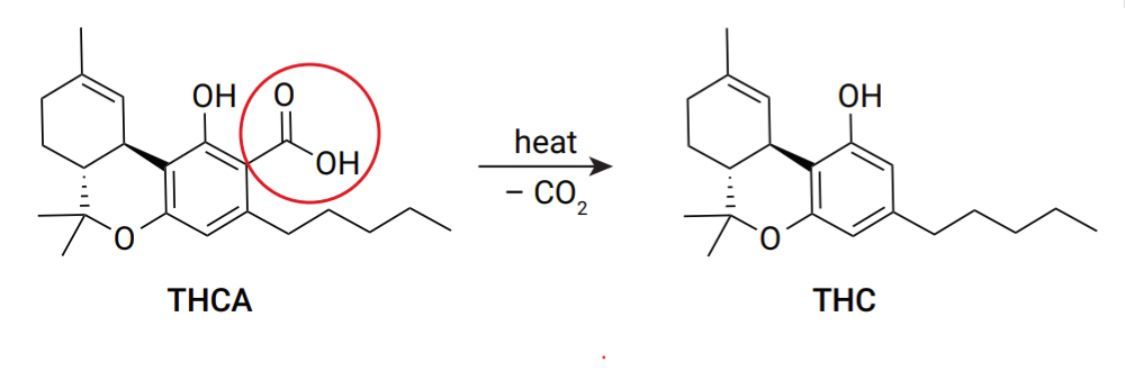

For example, if you purchase marijuana from a dispensary with a high level of tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the psychoactive ingredient of the plant, you can request the third-party, state-approved certificate showing the results of lab tests related to the batch that marijuana was originally in.

Many brands advertise their most potent marijuana flower to be 30% THC by volume. Labs can certify the marijuana has that level of potency. “It means that plant contains 300,000 parts per million of THC,” said Robert Brodnick, co-founder and CEO of Titan Laboratories, located at 2175 E. Valencia Road. “That means a third of that flower, the THC, is basically oil.”

Like other third-party testing labs, Titan is set up for testing of cannabis products, including determining the potency of marijuana plants. But as Brodnick and others explained, there’s a lot more the state requires labs test for than just potency and most of it is tied to making sure products are safe enough to hit dispensary shelves.

Testing for mold, pesticides

While Titan Laboratories is awaiting final approval by the Arizona Department of Health Services to start doing tests required by the state for products to make it onto dispensary shelves, Brodnick explained said the lab is already up-and-running for informational testing, which essentially is the same thing.

He also explained that there are five main categories of tests that the state of Arizona requires for every analyte (or test specimen), known as the Big Five: microbials, pesticides, residual solvents, heavy metals and potency.

“That’s pretty similar to what a lot of states test for,” Brodnick, who has worked in the marijuana testing lab industry in California and Hawaii, said. “Arizona did a really good job of having well-defined quality control.”

Each specimen, is subjected to the battery of tests, each calibrated to look for a different one of the Big Five.

In order to pass, or more accurately, not fail, the marijuana must meet specifications laid out in the Arizona Administrative code, according to Brodnick.

For instance, according to the code, in the “Pesticides” section, there are different allowable amounts in parts per million for a host of different pesticides. And just because a specimen, especially a marijuana flower specimen, might not meet standards at first, that doesn’t necessarily mean it “failed.”

Safety and remediation

It can be remediated.

In the case of marijuana flower that contains over the maximum allowable amount of a certain pesticide or microbial contaminate, the code advises to “remediate and retest, or destroy.” There are slightly different rules for remediation for different analytes, like edibles and concentrates, since those can’t as easily change form.

Remediation for marijuana flower can happen in a few different ways, said Will English, the other co-founder of Titan Laboratories.

“You could, for instance, send it through an extract process to turn that flower into distillates (distillates are products that contain high amounts of THC and other psychoactive compounds) and that extract process will almost certainly kill” anything, he said.

The tainted weed could also be remediated by being cooked and eventually turned into edibles. However, English confirmed there are some microbial contaminates, like salmonella, listed in the Arizona code, where remediation is not possible.

“If you see that? Must destroy,” English said. “No, there’s no remediation. You have to destroy that product.”

That’s not exceedingly rare, according to English and Brodnick. However, here in Arizona, they’ve found that the No. 1 contaminate to make it into analyte samples is a class of fungus typically called “black mold.”

“We’re kind of checking for it two ways,” English said. “One, we’re doing a direct test with it to see if that DNA is in there and we’re also checking for its toxins. Because that is a serious contaminant.”

How testing came to be

After doing $2 billion in sales in 2021 between its medical and brand-new adult-use recreational marijuana programs, it’s fair to say the state is in a green rush, raking in cash and producing cannabis. That can all be attributed to voters overwhelmingly approving Proposition 207 in November 2020 to legalize recreational use of the drug.

But along with new recreational marijuana and additional dispensary licenses being granted by the state in Proposition 207, earlier in 2020 the state passed legislation, Senate Bill 1494, making it mandatory that any retail product in Arizona be tested for potency as well as a battery of potential contaminants.

“The medical program has been around for almost a decade, but Nov. 1, 2020, was the first time that there was ever a state mandate to test,” said Sam Richard, executive director of the Arizona Dispensary Association, an organization that lobbied for the change in rules.

Most dispensaries, growers and producers adhered to a stricter, more professional testing regimen for their crops and products sold medical patients, Richard said.

But he conceded legislation was needed to ensure safety in the industry, even before recreational marijuana legalization, in the face of the state’s relatively large medical marijuana program.

For scale, according to the Arizona Department of Health Services, the department of administering and regulating both medical and recreational pot program in state, there are nearly 350,000 medical marijuana card holders in the state. That’s more than 4% of the state’s total population.

Now, with passage of Proposition 207 and SB 1494, the state is “this close” to bridging its medical and recreational testing regimes, Richard said. The differences come down to one or two different pesticides being on one list as not acceptable and not the other.

Either way, the increased testing is good for consumers, dispensaries and producers, and the industry at large, Brodnick said.

“Producers and customers want to know these things,” he said. “Because they see: better product, better market. But without the state testing, there wasn’t really a core requirement before that.”

READ MORE ARTICLES